The international football calendar keeps getting denser, which reduces considerably the number of out-competition encounters traditionnally called ‘friendly matches”. This evolution is welcolmed by those who think that “friendly matches serve no purpose” because of their lack of sportive stakes.

It is a mistake, because these matches are first and foremost encounters, and if many of them are harmless, they are still symbolic. Playing with the other is an act of exchange, share and confidence. It is the affirmation of equality before common rules without which the game would be meaningless. And in the case of football, so often compared to a “war simulacrum” and whose vocabulary is still riddled with warlike expressions, it is also a profession of peace.

Germany is about to play the thousandth game in its history. That is significant. In Europe, only England did better (1043) but it started 26 years before, in 1872, with the first “international” encounter against Scotland.

When Germany got a national selection, in 1908, it was still a Prussian empire (which by the way explains the black and white colors on its shirt). Since then, its team has been, more often than not, overloaded with symbolic significance. Not only in the numerous international competitions where it has done pretty well, but also in some “friendly matches”, organized explicitely under the sign of peace.

Three of them request a closer look.

Craving for recognition

The first one is the 199th game. It took place on November 22, 1950. Switzerland is the first one to agree to play a “friendly match” in a country banished from international football for many years, excluded from the first Football Wolrd Cup of the post-war period. The weather in Stuttgart is awful; but in the arena conceived to receive 60,000 spectators – and which, a fiew years before was still named “Adolf Hitler Stadium” – are squeezing in 110,000 people, up to the sideline all around the field.

From a security point of view, it’s completely irresponsible to start the game, but the collective thirst for this symbolic recognition of reintegration into the international community is too strong. As if the birth of a new Republic, a year before, was finally followed by its baptism.

Need for relaxation

Five years later, the 230th game takes place in the middle of summer, on August 21, 1955.

Everything has changed : the federal Republic is not only about to achieve its “economic miracle” of the post-war period, but its team even won, to everyone’s surprise, the 1954 World Cup in Switzerland. The Cold War pushed NATO to implement the adhesion of West Germany, and consequently, to enable it to start rearming as soon as May, 1955.

There is still a real question : what will become the 15,000 war prisonners, soldiers and civilians, that are still held in labor camps in the Soviet Union, in conditions that are “problematic” to say the least?

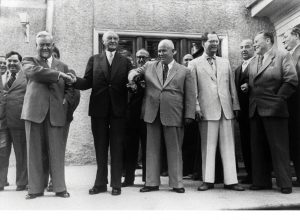

The chancelor Konrad Adenauer is about to go to the Kremlin to ask for their release. And it is there, just before his travel, that football takes the field, with a friendly match of the world champions in Moscow. How will react the Russian spectators ? Well, they end up giving a warm welcome to the two selections as they enter the field, presenting them with bouquets of flowers.

Match USSR – West Germany, 1955

There was no incident to deplore – quite the contrary. The Kremlin and the Chancellery are reassured, the visit will happen and the negotiations will succeed. Between October and January, all prisonners are able to come home.

Boulganine, Adenauer and Khrushchev, 1955

Affirmation of solidarity

The 1,000th game took place on June 12, in Bremen. To mark this special occasion in a 115-year history, punctuated by events engraved in the popular collective memory, the German federation had the elegance to invite Ukraine, a country whose one milion citizens are currently living in Germany. This choice was made, according to its president Bernd Neuendorfr “in order to send a clear signal in favor of peace and understanding between peoples and against war”.

A few days ago, I stumbled on Andriy Chevtchenko, the Ukrainian football legend, 2004 Golden Ball, on a visit in Paris. To my question about what he was thinking of this event, he answered that “it doesn’t matter if it is the 1000th game or the 990th, what counts in our situation is that the proceeds will be donated to social and humanitarian associations operating in Ukraine”.

He is not entirely wrong : the organisation of a football game, as symbolic as it might be, doesn’t win an armed conflict against a powerful agressor. In the meantime, this invitation to a “friendly” encounter not lacking in prestige or solemnity, makes accessible a solidarity commitment that is indispensable for the nation to which it is addressed.

This goes to show that friendly matches, after all, can serve a purpose after all.